I remember – as a small boy – reading a newspaper account of a Member of Parliament in which he was described as a statesman. ‘What,’ I asked my father, ‘is the difference between a statesman and a politician?’

I remember – as a small boy – reading a newspaper account of a Member of Parliament in which he was described as a statesman. ‘What,’ I asked my father, ‘is the difference between a statesman and a politician?’

My father thought about it for a moment or two and then said: ‘I suppose a statesman is just a politician of whom the newspaper’s editor approves.’ (This was back in those dim distant days of dark ink on paper.)

The dictionary definition of statesman is something like ‘a person skilled in the affairs of State; a distinguished and capable politician’. As I discovered, it’s one of those words that is always positive. There are no devious, scurrilous, or incompetent statesmen. If they are devious, scurrilous, or incompetent, they are politicians. Or worse.

A little later in life, I discovered that the word community is also always positive; while establishment is (almost) always negative. Fringe is at best suspect. And more often than not it’s dangerously loony.

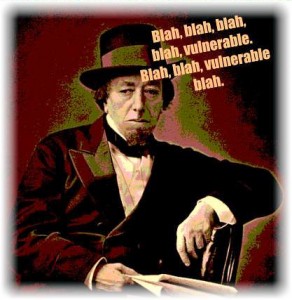

But perhaps the number one loaded word over the past few years has been vulnerable.

The dictionary definition of vulnerable is something like ‘in danger of being wounded or harmed’. But these days it has come to signal that any criticism of a particular idea or policy is out of bounds to all right-thinking people.

‘This policy is designed to protect the most vulnerable members of society,’ the politician declares. And, by using the word vulnerable, the politician has signalled that, far from being a legitimate challenge to the policy, any dissenting voice will be regarded as a dastardly desire to wound and harm.

I think it’s high time we stopped using vulnerable simply to protect vulnerable arguments.