With every house move, I manage to lose a few things. Not major things. Not especially important things. But things you end up missing anyway.

With every house move, I manage to lose a few things. Not major things. Not especially important things. But things you end up missing anyway.

Four moves ago, it was a linen tablecloth, a gift from an old friend. And a couple of moves later, it was the household’s number one teapot. The teapot was fashioned from heavy gauge stainless steel and looked rather like something that you might find in an industrial cafeteria. But it made uncommonly good tea.

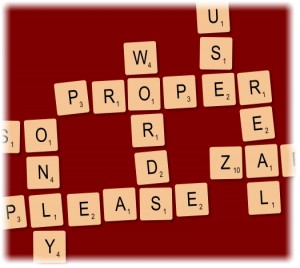

And then, in the course of the most recent move, I seem to have lost the Scrabble dictionary.

This is not the Official Scrabble Players Dictionary (or OSPD) sanctioned by the National Scrabble Association of the USA. It’s actually a Concise Oxford Dictionary from the early 1980s, to which has been added a distinctive Cambridge blue cover for easy identification. It is, however, official in the Scrivano household.

For as long as I’ve been playing Scrabble, there has always been someone at the table who insists that perfectly good words like fumarole (an opening in or near a volcano) and pangolin (a scaly anteater) are not real words. Under the Scrivano house rules, the challenger is entitled to look up the challenged word in the official (blue-covered) dictionary. If the challenge is successful, the word must be withdrawn. And if the challenge fails, the challenger loses a turn. It’s a system proven to discourage frivolous and vexatious challenges.

The only person I have ever played with who objected to our house rule was a lexicographer. Somewhat to my surprise, he thought that using a dictionary – any dictionary – to rule on what was or wasn’t a real word, was simply wrong.

‘Dictionaries are not the arbiters of which words are proper words,’ he said. ‘They are records of some of the words in use, together with some of the generally-understood definitions of those words.’

He went on to point out that the cut-off point for paper dictionaries had more to do with practicality than anything else. Using the two-volume Shorter Oxford English Dictionary as an example, he reckoned perhaps another 200,000 definitions might be included without descending into obscurity. But that would necessitate a three-volume edition. And that’s probably one volume too many for most people.

A few weeks earlier, a particularly well-read friend had tried to convince me of the legitimacy of syllabubous, meaning ‘having the texture or other qualities of syllabub’.

‘Would you have allowed that?’ I asked the lexicographer.

‘I see no reason why not,’ he said. ‘It’s probably not in any current dictionary. But I can imagine situations where it might be quite useful.’

Sorry, George. It seems we may owe you a Triple Word Score.