If you have ever started out to write a clear and concise instruction, proposal, or explanation, only to find that making it clear and concise was far from easy, you are not alone.

If you have ever started out to write a clear and concise instruction, proposal, or explanation, only to find that making it clear and concise was far from easy, you are not alone.

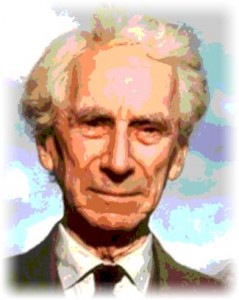

Bertrand Russell (a man who managed to express quite a few difficult thoughts and ideas clearly and concisely) once observed: ‘Everything is vague to a degree you do not realise until you have tried to make it precise.’

Or as a former colleague of mine was wont to say: ‘You don’t realise how little you know until you try to convey the little that you think you know to someone else.’

When I first started to earn a living as a writer, computers were machines the size of small houses, housed in special air-conditioned rooms, and tended by men in white coats. They were almost exclusively the domain of engineers and money men. We lowly writers composed our sentences on manual typewriters. Or, in the case of one of my colleagues, with a Black Beauty pencil on lined yellow ‘legal’ pads.

Typically, a first draft (often based on handwritten notes) would lead to a second draft, and a third, and sometimes a fourth. In the end, you had something that said what you needed to say and a waste basket full of not-quite-so-successful attempts.

Today, however, there’s a tendency to bang out something as quickly as possible and press the send button. Time is money. We expect everything to happen at the speed of light.

But if what you bang out is neither clear nor concise, the fact that you conveyed it at the speed of light counts for nothing. Sometimes it counts for less than nothing. If it doesn’t inform your reader, there’s a very good chance that it will misinform or confuse her.

Electronic wizardry has simplified and sped up much of the mechanical part of the writing process. But clear thinking and concise composition still requires time. In the interests of clarity and concision, make sure that you allow yourself enough time to think carefully about what you want to say, to say it, and then to make sure that you really have said it.