Many, many years ago, I managed to convince the powers that be at my secondary school that, rather than studying French or Latin in my fifth form year, I should be allowed to study art. As I recall, this encompassed drawing, painting, art history, and art criticism.

Many, many years ago, I managed to convince the powers that be at my secondary school that, rather than studying French or Latin in my fifth form year, I should be allowed to study art. As I recall, this encompassed drawing, painting, art history, and art criticism.

Tuesday and Thursday mornings I studied English – where we were encouraged to write lucidly, succinctly, and with a sense of style. Wednesday and Thursday afternoons I studied art – where the prevailing language was both gushily convoluted and mystifyingly opaque.

I quickly came to grips with the essence of clear and concise English. But I could never see the point of much of the language of art comment and criticism.

Many years down the road, I still find my English lessons useful. I still try to say what I have to say with clarity, simplicity, and an element of style. And yet – and perhaps I am reading in all the wrong places – the language of art seems to have become even more obscure, even more opaque.

Recently, I went to an exhibition of what might loosely be described as pottery. The pieces on display were more than competent. They showed a good deal creativity, and a real dollop of craftsmanship. Several made me smile. One even made me laugh. (Are you allowed to laugh in an art gallery? Now that I come to think about it, the woman behind the desk did look at me in a rather strange way.)

The day after my gallery visit, I was half listening to one of my favourite radio stations, a mainly-talk station that focusses on news, current affairs, science, and culture. And, in the ‘arts spot’, a woman was reviewing the exhibition that I had just been to see. Or at least I think she was.

The gallery’s name was the same. The artist’s name was the same. But the reviewer’s commentary sounded as if she was reading randomly-chosen passages from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake mashed up with randomly-chosen entries from the Oxford Dictionary of Foreign Words and Phrases. And she was doing it in a tone of voice that suggested that she was wondering why she was wasting her time casting her beautiful polysyllabic pearls before such unworthy swine.

Every trade, every profession, has its jargon. But if you are trying to communicate with a general reader (or listener), it’s usually best to put aside as much of the jargon as possible.

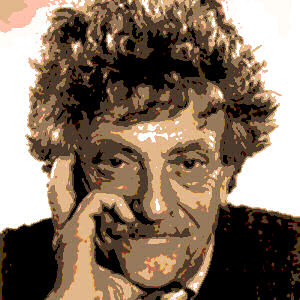

As the late Kurt Vonnegut advised students of his ‘Form of Fiction’ course at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop: ‘Do not bubble. Do not spin your wheels. Use words I know.’